BIOMECHANICAL TESTING

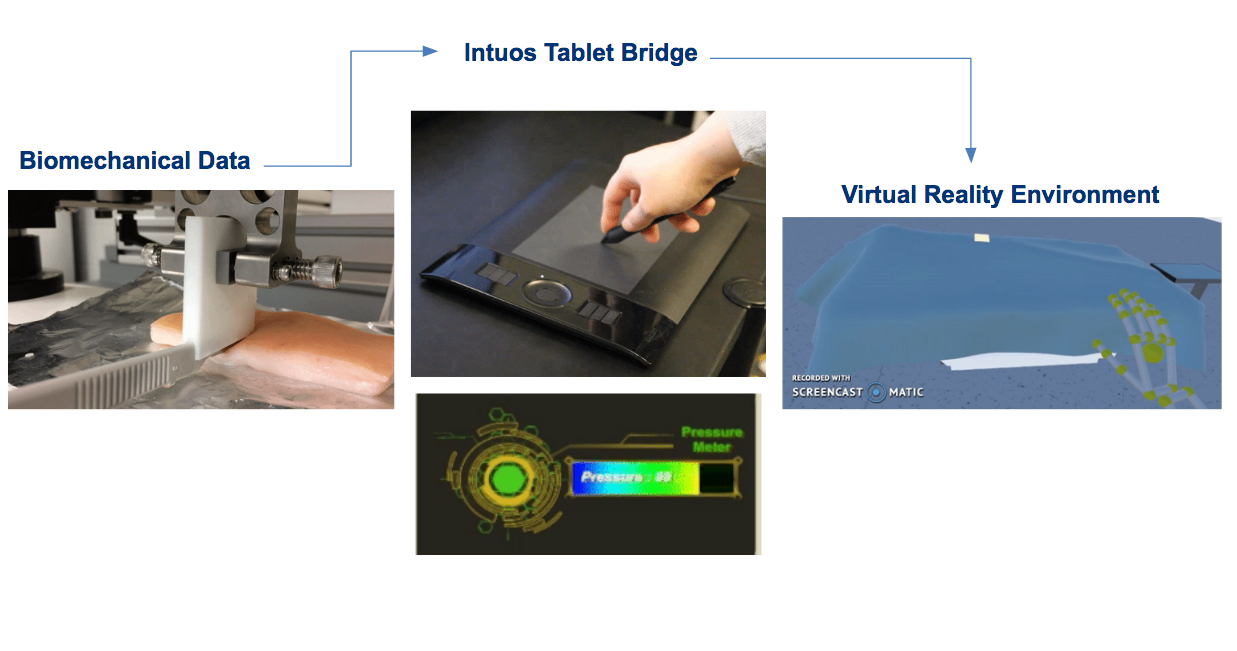

Collection of Data: Force Required to Pierce through Porcine Skin Samples - Development of a Testing Protocol and Associated Apparatus

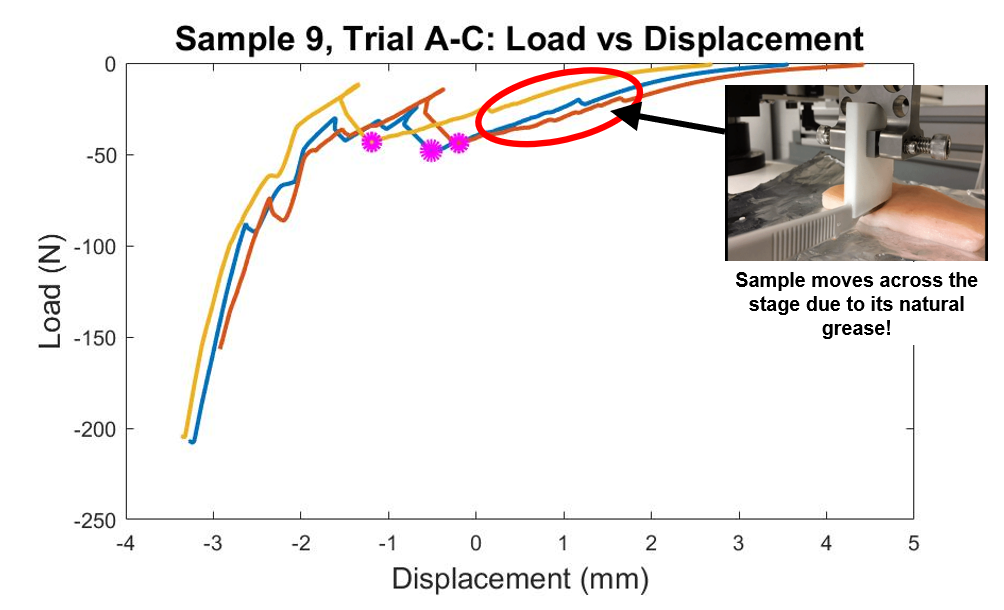

In an effort to collect data most representative of incising human tissue, porcine skin samples were used to mimic the human’s epigastric region. However, simply laying a slab of greasy pig skin on top of an Instron is neither sanitary, nor effective due to its, well, ridiculous amount of grease. Applying a downward force via the Instron would simply cause the sample to jiggle across the stage, resulting in erroneous data.

I know this because … well, we tried it with the BOSE system. You have to learn how to walk before you can fly, right? So our advisor at the time had us do this little exercise (which took about, oh, just an entire month) to teach us this lesson.

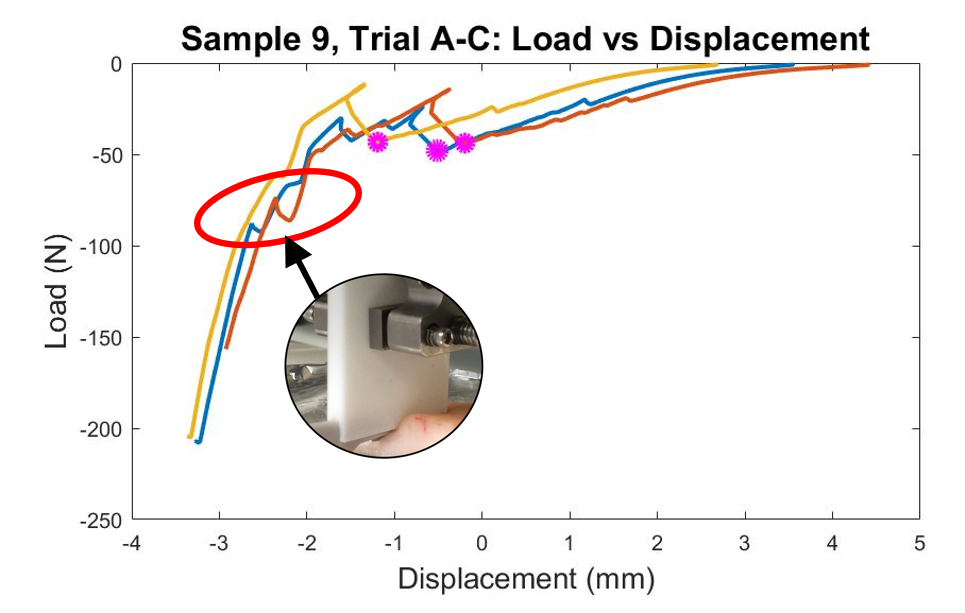

Of course, it wasn’t all for-naught. Correlating our sample’s initial dance moves with the resulting data-points revealed an interesting issue with our data: miniscule peaks and valleys across our graphs from other iterations of our mechanical test that we had actually thought held promise.

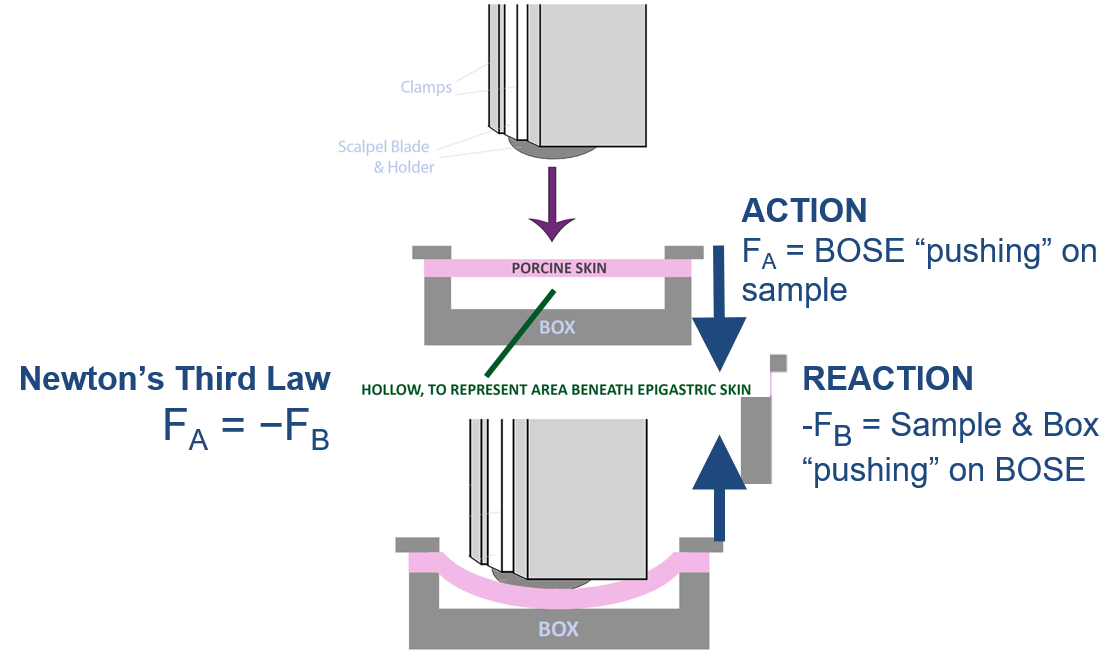

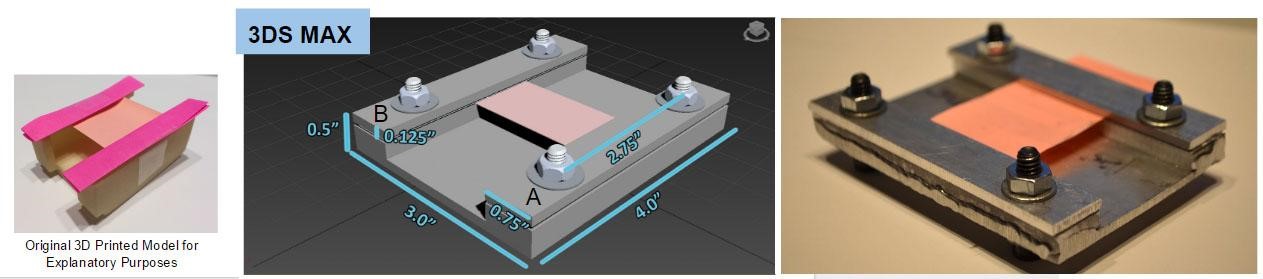

These “other iterations” were basically attempts at trying to model the human epigastric region as closely as possible. Take for example, the knowledge that our stomachs, in general (can’t speak for everybody!!), are muscular, HOLLOW organs. (Special thanks to PubMed Health for this information !). So clearly, laying a slab of pork skin atop the Instron was not mimicking the stomach’s hollow nature. We were advised to design and construct a box that would allow for the skin to be affixed to its ends, while also provided an area of empty space beneath it.

Footage of this test-run is as follows:

Throughout this journey of constructing an adequate testing environment, we were also confronted with the task of securing the scalpel blade to the Instron. Simply tightening the Instron’s clamps around the scalpel was not effective enough, as the clamps could not properly grip the scalpel. And so every time the scalpel was lowered to apply downward force, the blade would shift… yielding invalid data.

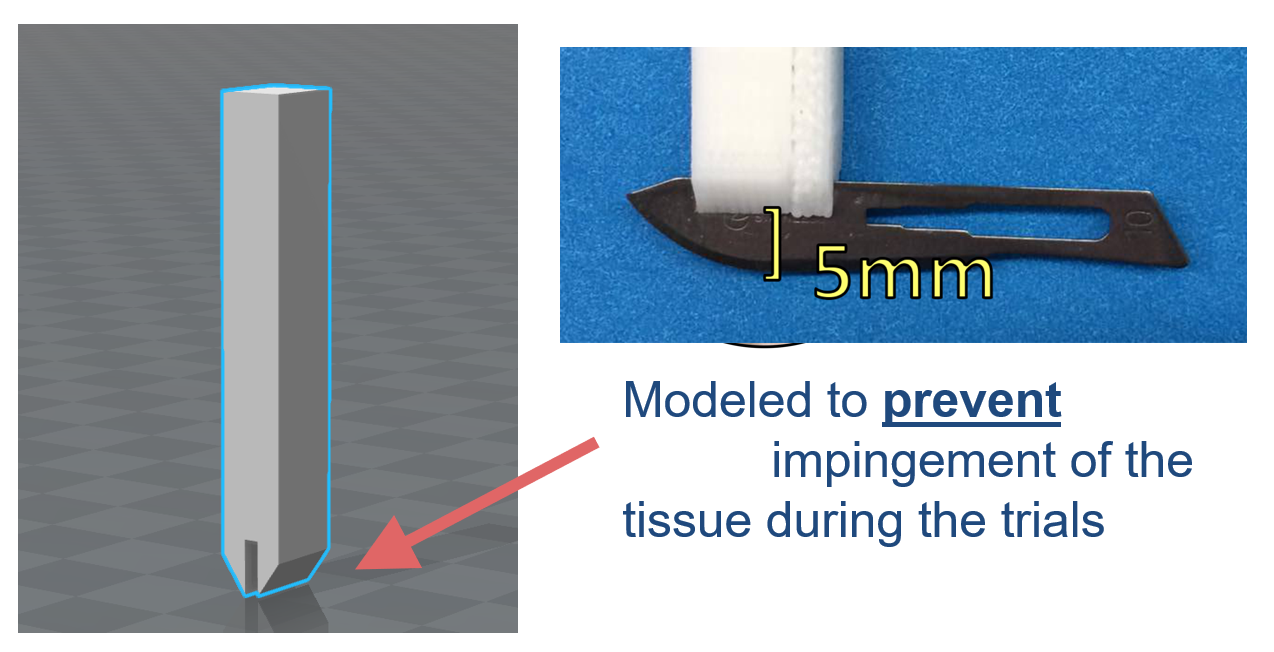

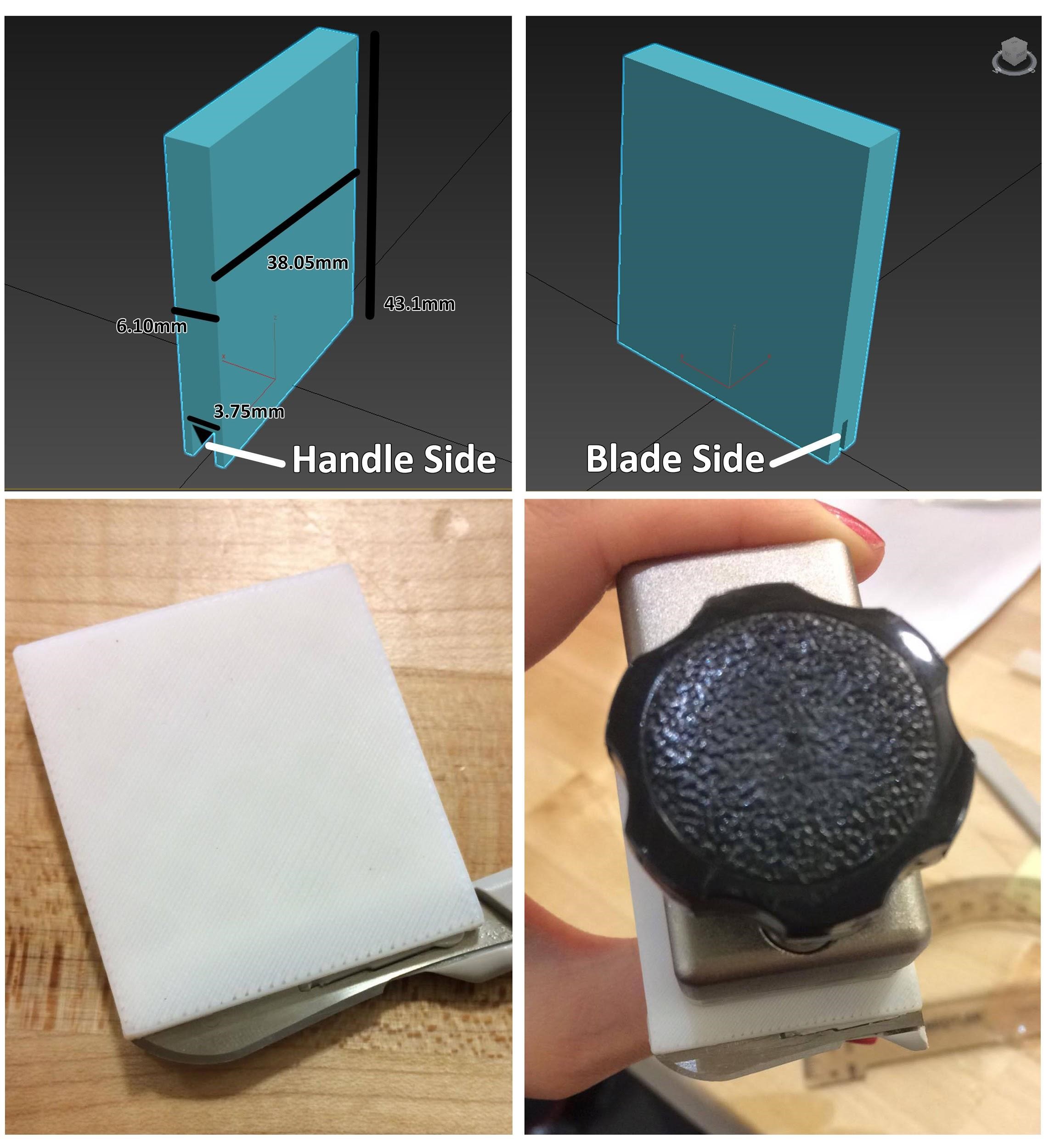

So, a scalpel holder was modeled, and 3D printed in such a fashion that it could snugly fit between the Instron’s clamps. The scalpel blades were removed from their handles, and epoxyed to these 3D printed holders.

Throughout the many iterations of testing, the holder’s design was also modified as we saw fit. Most notably was producing a more tapered bottom, since we found that the original design was impinging the tissue during compression testing, again resulting in erroneous data.

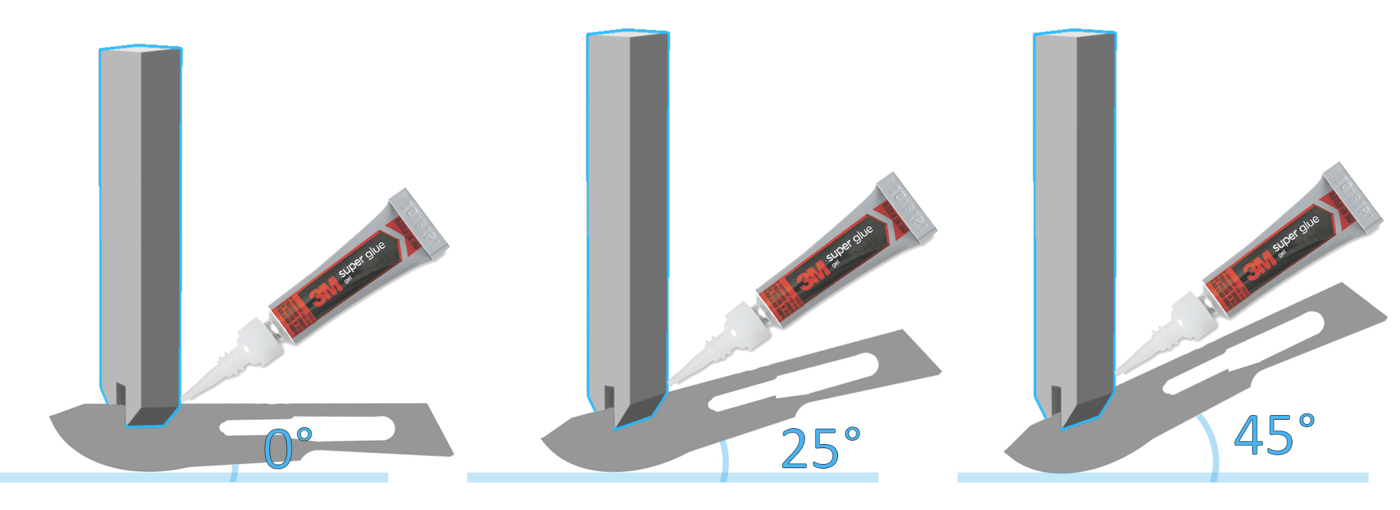

Utilizing a 3D printed holder also allowed for the blade to be epoxyed at different angles. This is important since it actually was found to be a major issue during residency training, and provided the motivation to begin this project in the first place. so that the force needed to incise tissue could be compared across scalpels at different angles; since that was a main issue according to the hahnemann study

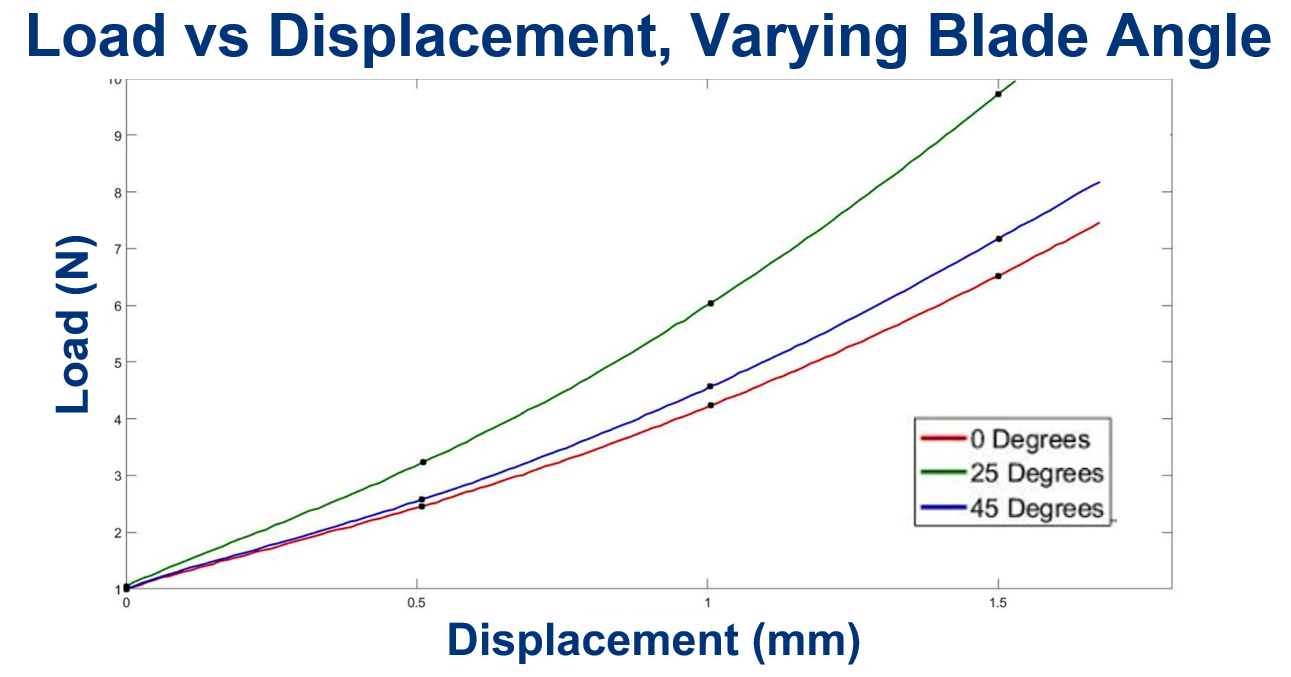

This experiment revealed the well-known fact that load varies by blade angle, and depth of penetration.